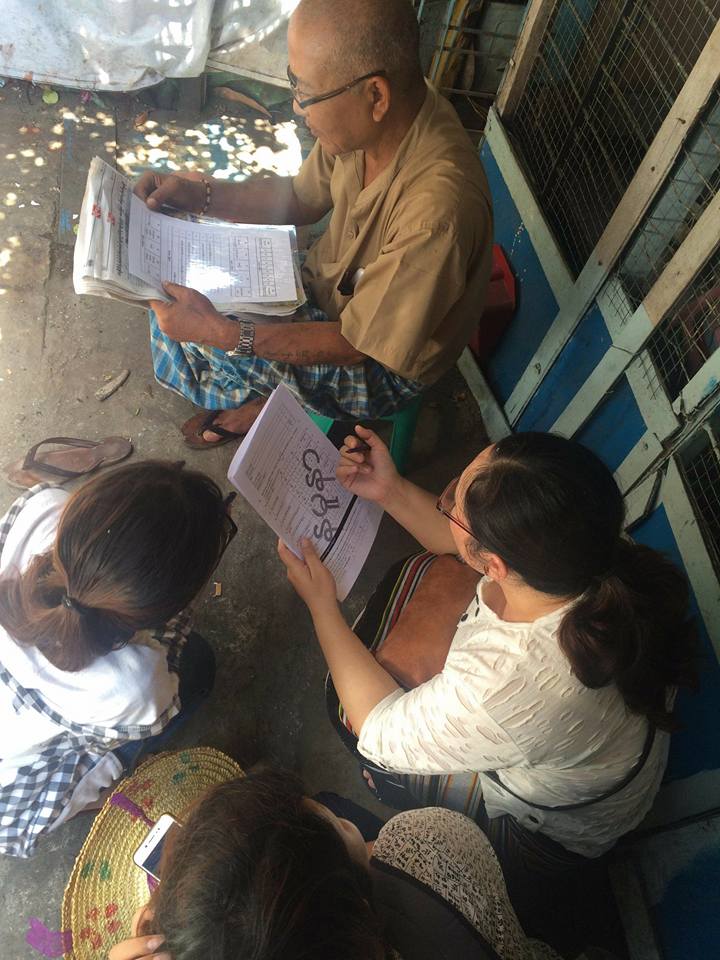

The 2016 post-electoral survey was the second nationwide survey conducted by PACE. To carry out the survey, PACE recruited and trained 167 volunteers to carry out the survey by randomly selecting households, conducting interviews and returning questionnaires to PACE. Six two-day enumerator trainings were conducted in Yangon and Mandalay and included interview role-plays and practical exercises in household and respondent selection.

Additionally, 17 state/region coordinators were assigned to oversee the work of enumerators. Finally, 15 volunteers were trained to conduct data entry for the survey findings.

The Goal of Survey

PACE conducted the post-election survey to identify priorities for electoral reform and to identify knowledge gaps in civic education by probing:

Public’s attitudes and opinions about democracy and elections

Public knowledge and views towards priority issues on the electoral reform

Public awareness and expectations towards the political institutions and the newly elected officials

In Myanmar’s November 2015 elections, 69 percent of people turned out to vote according to the Union Election Commission (UEC). More than 10,000 people mobilized to observe election-day and dozens of organizations conducted voter education during the electoral process -- a sign that citizens were finding new ways to be involved compared with past elections. Although the public generally accepted the results of the election, there remain a number of challenges in the country’s political transition, including debates around the constitution, negotiations around the peace process, and the democratic culture of the country.

Attitudes and Opinions about Democracy and Elections

Interpersonal Trust

The level of interpersonal trust is often measured in public opinion surveys to demonstrate quality of social, economic and political relations between people in a society. PACE asked respondents if they thought “most people can be trusted OR that you need to be very careful in dealing with people?”. The majority of respondents (55%) believe that you must be careful with people, while only 37% believe that most people can be trusted and 8% said they did not know.

There are no significant differences in levels of trust between respondents from states and regions, urban and rural, and men and women. However, as shown below, young respondents were less trusting than older respondents. Similarly, higher educated respondents were less trusting than less educated respondents respectively.

Communal Engagement

Respondents were asked how often they participated in community groups, sports groups and worker associations. This question is commonly used to measure levels of communal engagement in surveys conducted in other countries. As the table below shows, more than half of all respondents exhibit a low level of communal engagement, while an average of less than 20% of all respondents demonstrate a high level of engagement.

Opinions on the Status of Human Rights

PACE asked respondents “How much respect is there for human rights nowadays in Myanmar?” Most respondents said there was a lot of respect (17%) or some respect (47%) for human rights. Fourteen percent (14%) said there was not much respect for human rights, while 3% of respondents said there was no respect. Eighteen percent (18%) of respondents said they did not know. Notably, there was little difference in respondents from states and regions in their view of the status of human rights in Myanmar.

Perceptions of Government Responsibility for Human Rights

To understand citizens’ views of the role of government in maintaining human rights, PACE asked respondents “Which would you say is the government’s most important responsibility: a) To maintain order in society? OR b) To maintain freedom of the individual?”. Nearly two-thirds (63%) of respondents agreed that the government’s most important responsibility was to maintain order in society, while 25% said it was to maintain freedom of the individual, and 12% said they did not know.

Respondents from regions were more likely to say that the government’s primary responsibility was to maintain order in society. Respondents with a lower educational background were more likely to say they did not know, possibly indicating a need for more targeted civic education on the role of government.

Perceptions about the role of citizens

PACE assessed respondents’ views on the roles of citizens by asking them to choose between the following statements: Statement 1: “Citizens should be more active in questioning the actions of national leaders” and Statement 2: “In our country, citizens should show more respect for authority.” Almost two-thirds of respondents either strongly agreed or agreed that citizens should question their national leaders, while a total of 26% of respondents either agreed or strongly agreed that citizens should show respect for authority. Respondents across all demographics shared the same view on the role of citizens.

Interest in Politics

Interest in politics is important because it provides the motivation for citizens to become informed. PACE asked all respondents the standard question: “how interested would you say you are in politics?”. The majority of people are interested, with 16% saying they are very interested and 42% saying they are somewhat interested. The remainder of respondents said they were not very interested (18%) or not at all interested (15%). A further 9% of respondents said they did not know.

Male respondents were more likely to be interested in politics than female respondents.

Respondents living in urban areas said they are slightly more interested in politics compared with rural respondents.

Overall, interest in politics has increased since PACE asked the same question one year before in 2015. PACE notes, however, that interest in politics has decreased slightly since the immediate post election period. Immediately after the election, the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) conducted a survey from December 2015-January 2016 that reported that a total of 72% of Myanmar citizens reporting to be very or somewhat interested in politics compared with 58% in PACE’s survey conducted four months later.

Citizen Participation

PACE wanted to measure how active and interested citizens were in political and civic activities in their community. They asked respondents if they had attended a community gathering, attended a voter/civic education meeting or signed a petition in the past year.

Overall, respondents indicated that they were not very active in these activities over the past year, especially in voter/civic education and signing petitions. More than half of respondents had not participated, however the majority said they would if they had the opportunity. In general, citizens show more willingness and interest in the traditional and more common activity of community gathering compared to newer activities like voter education or signing a petition. More than half of citizens said they had never joined a voter or civic education meeting, despite the fact that elections were held last year.

Rural respondents were more likely to engage in community gathering than urban respondents as were older respondents compared with youth respondents.

Women were less likely than men to participate in community gatherings, potentially showing the need for greater promotion of their participation.

Respondents who said they are interested in politics were more likely to attend a voter education meeting.

Participation in the 2015 Elections

According to the Union Election Commission, 69% of voters cast a ballot in the election. PACE asked respondents why they did or did not vote.

Among respondents who said they voted, PACE asked “What was the main reason you voted in this election?” Most voters saw the election as a means to express their political view: either to support a party or candidate that they like (25%), express their opinion (16%), or choose their representative (5%). Others saw voting as an important role of citizens: 22% said they voted because it is a civic duty, while another 15% said it is important to vote. There was no notable difference in the motivation of voters between ethnic states and regions or between men and women.

Among respondents that said they did not vote, PACE asked “What was the main reason you DID NOT vote?” Less than one third of respondents said they did not vote for reasons of apathy: 21% said they did not vote because they were sick or busy, while nearly 8% said they did not care. Other respondents said they did not vote due to issues accessing the electoral process, with 17% saying that they were registered far away from where they lived, 16% saying their name was not on the voter list, and 10% saying they lacked required identity documentation.

There were differences for non-voting in states - where respondents more often noted issues in accessing the election process - compared to regions - where respondents more often noted reasons of apathy.

Notably, women were much more likely to say they did not vote because they were busy or sick on election day.

Among respondents who did not vote, twenty-two percent (22%) of youth respondents said they did not vote because their registration place was far from where they live compared with 14% of older respondents. This could be related to the number of youth who live far from their home of origin due to work or study. On the other hand, older voters were more likely to say that they lacked sufficient identity documents.

Knowledge and Opinions on Priority Issues for Reforms

In order to measure public knowledge and views towards priority issues for electoral reform, PACE asked respondents a number of questions about their views of the 2015 elections and their priorities moving forward.

Knowledge about Independent Election Observers

PACE measured the public’s knowledge of independent election observers by asking if respondents “recall hearing of any independent civil society election groups in the last 2015 elections?” More than half of respondents (53%) said they had heard of independent civil society election observer groups, while 37% said they had not and 10% said they didn’t know. This is a slight increase from PACE’s 2015 pre-election survey, in which 46% of respondents had heard of election observers.

Respondents from states were less likely than those in regions to know about election observer groups. Similarly, women were less likely than men to know about election observation groups.

Perceptions of the Effectiveness of Election Observers

PACE also asked respondents if they believed that the involvement of domestic observers and international observers could “help guarantee transparent elections.” More than two thirds of respondents said they thought observers could be helpful, with domestic observers seen as slightly more helpful than international observers.

There was a significant increase in the percentage of the public who believe that independent election observers can guarantee transparent elections since PACE asked citizens in May 2015.

There was no significant difference between socio-demographic groups on the perceived effectiveness of observers. However, if respondents already knew about election observation groups, they were more likely to consider them useful for guaranteeing transparency in elections.

Trusted Sources of an Objective Assessment of the Election Process

To learn where citizens look to decide the quality of the election process, PACE asked respondents “Who do you trust most to provide you with an objective assessment of the election processes?”. Most respondents said they did not know who they could trust to provide an objective assessment of the elections. Notably, less than 5% said they look to observers to provide an objective assessment of the election process. While there was no difference between respondents from states and regions, there is a significant gender gap in the number of women respondents who said they do not know.

Levels of Satisfaction with the 2015 Elections

PACE asked respondents “How satisfied are you with the 2015 ?”. Overall, respondents were very positive about the elections: More than half of respondents (52%) said they were very satisfied with the process, while 35% said they were somewhat satisfied. Only 5% of respondents were somewhat or very unsatisfied, while 8% said they did not know.

However, among respondents from states, there was a slightly lower level of satisfaction with the election compared to respondents from regions. Men were more likely to say they were satisfied than women.

Public Opinions about Need for Reforms in Election Process

PACE also asked respondents if there is “any aspect of the 2015 election process that could be improved in the future?”. More respondents believed there is need for improvement, with 40% saying there were aspects that could be improved, 32% saying there were not and 26% saying they didn’t know.

Respondents from urban areas were more likely to say there was a need for reform compared to rural respondents. Women were more likely to say that they did not know if there was a need.

Of those respondents who noted a need for improved election processes, PACE asked “what specifically do you think could be improved in the future?” recording up to three answers. Sixty-one percent (61%) respondents pointed to the voter list/voter registration as an area for improvement, while 37% noted election day management, and 35% said civic and voter education needed improvement. Electoral fraud and the structure and appointment of the UEC and its sub-commissions were also frequently mentioned. Although they said there was a need to improve elections, a quarter of respondents said they did not know what specifically could be improved.

States and regions have different priorities for electoral reform. Regions are more concerned with the voter list and civic education than respondents from states. On the other hand, respondents from states were more concerned with advanced voting than citizens from regions.

Views on Important Qualities for Election Commissioners

As the new Union Election Commission is forming at the national and subnational level, PACE measured the public’s views on qualities that are important in that role. PACE asked respondents “What do you think are the most important qualities that a good election commissioner should have?”. One third of respondents said that integrity and trustworthiness are most important, while 18% said experience and expertise were most important and 8% said independence.

Awareness and Expectations towards the Political Institutions and Newly-elected Officials

Public Understanding about the Method of Electing the President

To gauge the level of civic knowledge Myanmar’s executive branch, PACE asked respondents if they know how the President of Myanmar is elected. Only 12% of respondents correctly answered that the President is elected by the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw , while 19% said that voters directly elected the President, 17% said that the party who won the most seats appoints the President, and 48% said they did not know. Women were less knowledgeable than men about how the president is elected.

Knowledge of Government Officials

To measure citizen knowledge of their government representatives and officials, PACE asked respondents: “Do you happen to recall the name of (a) the ward/village tract administrator; and (b) the newly elected member of Pyithu Hluttaw for this constituency?”

Less than a quarter have high-knowledge of their officials, correctly naming both their representative in the Pyithu Hluttaw and their local administrator. Male respondents have a slightly higher knowledge index than female respondents.

The majority of people can name their local administrator (73%), while only 25% can name their member of the Pyithu Hluttaw. More rural people could name their local official than urban.

More people could name their MP in 2016 than people in 2014, when The Asia Foundation (TAF) asked a similar question in its national survey. The percentage of people who can name their local administrator decreased slightly since 2014. PACE believes there was a slight decrease because a number of ward and village tract administrators were recently appointed during the time the PACE survey was conducted. Men were more likely to know the name of their MP than women.

Awareness of MP Activities

PACE asked respondents if they “are aware of any meetings/activities organized by your newly elected MPs in the past 5 months?”. Only one quarter of respondents said they had heard of activities by the MP in the last 5 months (January-May 2016). Nine percent (9%) said they participated personally.

Public Expectations about the Role of MPs

PACE wanted to know how citizens view the role of Members of Parliament. PACE gave respondents a list of ways in which Members of Parliament spend their time and asked them to identify which was most important and which was least important. Twenty-two percent (22%) of respondents said that actively participating in parliament sessions was the most important role of Members of Parliament, while 21%said mobilizing development activities in their constituency was most important, and 14% said visiting and hearing from their constituency was most important.

Public Opinion on Priority Issues for the New Government

PACE also asked respondents about problems faced by Myanmar as a whole that the new government should address. Most respondents said that peace and armed conflict was the top priority facing the country (41%), while education (23%) and infrastructure (18%) were also common issues.

It is notable that 50% of respondents said they “Do not know” which national issues should be addressed, compared with 25% of people who answered “Do not know” for local issues. Rural respondents, women and people from ethnic states were more likely to answer “do not know” about national issues.

Respondents from states and regions mentioned different priorities, with people in states giving higher priority to peace and armed conflict and infrastructure than those from regions. At the same time, respondents in regions placed higher priority on environmental impact of industries, unemployment and land issues.

Public Confidence in Institutions

PACE asked citizens how much confidence they had in public and private institutions. Respondents had the most confidence in religious leaders (80%) and the President (79%). Civil society and community-based organizations held the confidence of 68% of respondents, while the Union level parliament held the confidence of 62% of respondents.

When looking more closely at how electoral stakeholders are perceived between demographics, different groups had varying levels of confidence in institutions. For example, respondents in states indicated they had less confidence in electoral actors than respondents in regions.

Women were also less confident in key institutions, such as Union-level parliament and the UEC, and they were more likely than men to say they did not know how to answer.